- Home

- Chris Wraight

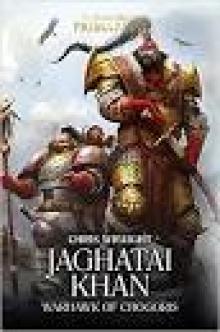

JAGHATAI KHAN WARHAWK OF CHOGORIS Page 8

JAGHATAI KHAN WARHAWK OF CHOGORIS Read online

Page 8

‘No.’

That was the most usual answer. The Test of Heaven, the esoteric rite taken by those who became the shamans of the tribal nations, was usually taken too late for candidates for the Legion, so it was more common to discover physical promise in recruits, and only later detect psychic ability. Those recruits faced the hardest trials of all, their body, mind and soul all tested to the limits of destruction before new strength could come.

Yesugei glanced at the smouldering ruins of the image, looked over the swirl pattern in the sand, then grunted in approval. ‘You have learned quickly. Tell me, what do you feel, when you do these things?’

‘I do not–’

‘You understand me. What do you feel?’

Borghal hesitated. Then he lifted his head to face Yesugei. His brown irises were already lightening, fading to an amber that would one day, if he survived long enough, become gold. ‘Power,’ he said.

Yesugei nodded. ‘Yes. That is the danger.’ He placed his calloused hand on the acolyte’s shoulder. ‘Power is what you already have. We bring you here to leash it. We bring you here to make this thing as natural to you as breathing, and as swift. If that creature had been real, it would have ripped your heart out while you were speaking the rite-words. It is not about power. It is about limitation, and then understanding.’

The acolyte nodded, chastened.

‘But the strength cannot be denied,’ said Yesugei, grinning at him and slapping his hand on his shoulder. ‘You will be formidable. Just stay alive a little longer, please – I would like to see you use that in the Crusade.’

Borghal bowed. The attendants ventured onto the sand to clear away the wreckage, and the two Stormseers moved off, walking back towards the double doors, passing under the sharp shadows of the plane trees.

‘They are getting better,’ said Yesugei. ‘My congratulations.’

‘And yet, when we train them, we do not know where to place them,’ said Naranbaatar. ‘You cannot leave it to the khans. It has been too long since we last argued over this.’

‘And the answer remains the same.’

‘That the Khan must decide. When will that–’

‘He is coming. Soon.’ Yesugei looked at his deputy. ‘He has had years of fighting now. He has seen worlds burning at his hand, a hundred of them. He wishes to accelerate the pace of conquest. This is only a part of what he plans.’

‘I could give him a hundred weather-makers this day. They could level any wall for him. They could rip the galaxy apart.’

Yesugei smiled sadly. ‘If it were that simple, if we were alone in the Imperium, there would be little need for debate, but we are not. The Khagan has his brothers, and there is the distant gaze of Golden Terra. These things must be managed.’ They reached the doors, and the hazy screen of incense became briefly pungent. ‘There is one, calling himself the Lord of Death, who is master of a Legion of terror troops as formidable as any scion of the Throne. I studied his doctrine from afar, admiring some of it, repelled by the rest. He is damaged, I think, but that matters not – we are all damaged, in some way or other, and his effectiveness is not in question.’

Naranbaatar listened.

‘He has forbidden the use of sorcery within his ranks,’ Yesugei said. ‘Purged it. He has a following at the Terran courts, and powerful voices within the Imperial Army have been raised in his support. That should not surprise us. This is, after all, the message of Unity. We are the outliers.’

‘It is only one Legion.’

‘There are others. The Wolves of Fenris, though I do not entirely understand their position, since there are rumours of gifted individuals among them. The tally grows. Though we endeavour to remain isolated, one day we will have to fight alongside all of them.’

Naranbaatar looked back over to the training ground, watching as another acolyte was put through his paces by the instructors. The air began to fizz again, its constituent parts being stressed beyond endurance by the release of energies from the far side of the veil.

‘We have never looked to others for approval,’ he said.

‘It will have to be settled.’

Naranbaatar shook his head. ‘We should ignore it. Let it pass us by.’

‘Perhaps. That may be what the Khan orders.’ Yesugei looked pensive. ‘But there may be strength in numbers, a way to preserve all this – that is the matter at hand. It is why he returns.’

Naranbaatar thought about that for a moment. The ritual words of summoning drifted over on the air, uttered by the next acolyte in a long line. Just as had happened for millennia on Chogoris, the ways of the weather-maker were being learned, honed, extended.

‘And so,’ he said, eventually, ‘will he meet this Lord of Death, then?’

‘Not by choice.’

‘But he is important to this, or you would not have mentioned him.’

‘I do not know. Truly.’ Yesugei turned back to the doorway, and the lintel’s shadow fell across his face. ‘We are storm weavers, not future readers. Who really knows? It may be nothing, or it may be everything.’

He went inside. Naranbaatar followed him in, smiling dryly.

‘Conclusive as ever, then,’ he said.

EIGHT

Two days later, the Swordstorm entered Chogorian orbit. It was not alone – Hasik’s vessel, the Tchin-Zar, came with it, as did half a dozen lesser craft. Like most Legions, the White Scars had grown both in numbers and commitments as the Crusade entered its apogee, and the fleet had expanded to accommodate the burgeoning capability of the Khan’s tactical forces.

They were the great years. The majority of the Emperor’s sons had been located and given command of His sundered forces, and the pace of expansion was faster than it had ever been. The forges of a hundred Mechanicum worlds struggled to supply the Imperium’s war hosts with the ammunition they needed, let alone the vessels, the armour and the weaponry. The known galaxy, once a barely charted haunt of terror, was swiftly becoming humanity’s realm, compassed by its unmatched numbers, technology and martial organisation. Planet after planet fell, was fortified, made compliant, then made productive.

The White Scars had played their part in this. They had pushed a little further than the others, perhaps, taking on those campaigns that would see them rove far ahead of the main lines of command and control, outpacing the lumbering expeditionary fleets in their zeal to blaze new trails into the distant void. In most cases, they fought alone, and thus developed a reputation for either flightiness or aloofness. They also gained a similar reputation for unreliability, especially within the senior hierarchy of the Administratum. Envoys were sent out from Terra, one after the other, each charged with improving relations with this most frustrating of primarchs, but few even made it to their intended destination, let alone succeeding in their mission. What chance did they have, set against a Legion of wild-riders gifted some of the finest ships in the Imperium, and who remained stubbornly resistant, in all ways, to governance from a centre they had only ever been distant from?

For all that, the worlds continued to tumble, one by one, into the hands of a willing Administratum. Such was the rate of conquest, speculation began to spread across the war fleets on what would happen once there were no xenos left to annihilate. Even those who held such a prospect implausible began to detect a change in the tenor of the campaign. Survival for the species had now been secured, so it seemed. The Emperor, beloved by all, would no doubt unveil the next move in His ongoing plan at some stage, though what form that might take was unknown to all but His closest ministers on Terra.

It was in such circumstances that, as the storm-lashed sun sank below the horizon west of the Khum Karta, the lord of the V Legion returned to his home world, the first such visit for many years. The walls of Quan Zhou were hung with the banners of conquest, each given a calligraphic symbol denoting another world or another culture destroyed. The preserved heads of conquered xenos races lolled emptily from stakes lining the processional avenues into the fortress�

� central bastion. When the Khan touched down in his hawk-prowed lander, the thousands of Legion warriors undergoing training called out in ritual greeting, sending the massed roar – Khagan! – booming out into the turbulent skies.

Even out on the plains of the Altak, where black-curdled thunderclouds were racing and the inhabitants had no knowledge of the galaxy’s tribulations, khans lofted their curved blades to the heavens and saluted the fire streaks making the distant mountain ranges glow. The zadyin arga knew. They knew that the world’s master was among them again, ordering the pillars of the earth and ensuring the souls of his people would remain unsullied. Beasts were slaughtered that night, and couplings solemnified, and old feuds were laid to rest for a little while. It was not proper to kill in anger on such a night, and nor would it be until they felt in their blood that he was gone again, to wrestle with the powers of the oververse and contest the arch of stars against the element daemons and soul dragons that haunted the realm of the unseen.

As the Khan trod the embarkation ramp and emerged out into the light of a thousand torches, Yesugei was there to greet him.

‘Pleased to be back, Khagan?’ the Stormseer asked.

The Khan drew in a long breath, pulling the cold air of Chogoris deep into his lungs. The first rain from the coming storm was already beginning to fall, spattering wind-scarred stone and making the mountain’s forest mantle shake and brush. The primarch’s battleplate still bore signs of combat yet to be excised by the Legion’s armourers, and thick rivulets from the gathering downpour ran down its ceramite curves.

He looked up at the peaks, frost-blue against the gathering storm, and smelled the pine-sharp, moisture-laden air. Both moons had risen in the eastern sky, full and silver, and it made the hurtling clouds look like the bucking spines of equines.

A weight seemed to lift from him.

‘By the gods, yes,’ he said.

The Legion mustered that night in the Hall of Jasper, a great chamber hollowed out at the heart of Quan Zhou’s ceremonial maze. Fires leapt from deep pits placed in the stone floor, sparking from incense and sending multihued plumes of smoke curling towards a high-arched wooden ceiling. Long rolls of crimson silk swung from iron banner-poles declaiming deeds of the Legion in formal poetic screeds. Attendants brought platters of food and drink, each of them dressed in the various garbs of Chogoris’ melting pot of cultures – sequined Qo gowns, fur-lined Khitani robes, or Talskar, Kurayed and Mathuli deels and kaftans. Music from moon-shaped lutes drifted across the hubbub of conversation.

The Khan took his place at the high dais, flanked by his captains. Before him lay a wide open space of worn flagstones, each one taken from the old courtyards of Ketugo Suogo’s palace – the man Imperial remembrancers had called the Palatine – transported from the eastern littoral and re-set within the mountain fastness of his conqueror. On all three facing edges sat warriors in ceremonial white robes, their faces bronze in the firelight, their salvers piled with near-raw meat.

Two Legion fighters circled one another out in the open, each carrying a blunt-iron blade. One wore a black jerkin, the other gold. Their faces, both marked by the long ritual scar, were fixed in pure concentration. The warrior in gold was a little taller, the one in black a little wirier, but otherwise they might have been mirror images.

The Khan watched them carefully, reclined on a plains-throne smothered in furs, chewing. Hasik, placed at his side, threw back a cup of rosewine and beckoned for more.

The gold warrior moved first, swinging into a strike. The black responded instantly, drawing away and pushing the counter-move. They danced around one another, limbs blurring, blades blurring, two shards of colour in the wavering blood-light. Each seemed to know the location of the perimeter by instinct, never straying too close but making use of every morsel of space within the prescribed zone.

The fight progressed longer than many that had gone before. The conversations died down; the music faltered and gave out. Soon the only sounds were the grunts of effort, the skidding of leather-bound feet on gravel and the whistle of blades over and under one another. Sweat flew in spatters. When the heavy blades – sparring instruments based on the straight-edged infantry weapons of the Kuzil nation – clanged together it was only for a moment. The contest was to first blood, and was a test of concentration and agility rather than raw strength.

Hasik leaned closer to the primarch. ‘Watch the gold.’

There was little to choose between the warriors, but the practised eye knew what to look out for – a faint edge of decisiveness, of accuracy, a sliver more weight to a blow and a fraction less time taken to recover from a hard parry.

Both warriors fought with commitment, and both were skilful, reservoirs of endurance and resolve. But Hasik was right – the one in gold was just a little further along the arc towards perfection. His opponent began to pant harder, to work harder, straining for some way past the glittering screen of his opponent’s solid defence. They spun around, faster and faster, their heels barely touching the sand. Murmurs of appreciation came from the audience as more time passed without a mistake – the focus was absolute, the commitment total.

Then the warrior in black slipped – just by a hand’s breadth, a short scrabble through the grit, swiftly checked, but it was enough. The gold figure pounced, slamming his opponent’s blade aside and pressing the advantage. A second later, and the black-clad warrior was on his back, his sword loose in his hand, the tip of his counterpart’s weapon pressed against his bared neck.

There was no rhetorical flourish, just a swift flick of the point, searing a line of blood across the defeated fighter’s collarbone. The audience roared its approval, thudding the low tables and raising flasks of halaak to the winner.

The defeated warrior’s muscles went limp. He hauled in great, heaving breaths, his body taken to the limit, his limbs trembling from exertion.

The victor was little better off. He saluted to the Khan, face dripping, looking unsteady on his feet. The acclamation seemed to buoy them both, though, and after a moment he reached down to pull his comrade up from the floor. Their swords thudded to the ground, and they clasped hands firmly at the wrist in the Chogorian style, exhausted.

‘From your Horde?’ asked the Khan.

Hasik shook his head. ‘The Brotherhood of Summer Lightning.’

‘What clan?’

Hasik shot him a sly look. ‘None. He’s Terran.’

For a moment the primarch looked nonplussed. He stared at the warrior in gold, who was staggering over to the nearest table and demanding drink in flawless Khorchin. Everything about him – the way he looked, the way he fought, his poise and his resilience – spoke of a son of the Altak. His skin had the same copper sheen, his hair the oil-black thickness, wrapped in a ceremonial topknot. The old khans sometimes spoke of ineed – the kill with cheerfulness, the unconscious fluency of violence – and assumed that only a Chogorian could possess it.

‘What’s his name?’ the Khan asked, intrigued.

‘When he came to us, Luthian. Now he’s ascended, they call him Jubal.’

The Khan shook his head. ‘I would not have believed it.’

‘Remember that first day on Terra?’ Hasik was laughing now, his face flushed from the food and the alcohol. ‘They were like armoured bears. Now we breed them into hawks.’ He grinned, and took another swig. ‘I told them you’d change them. I told them you’d remake them, like you did us. It’s completed, Khagan. We’re all White Scars now.’

The Khan took more drink himself. That had been the objective, set all those years ago. Terran recruits would continue to arrive for decades to come, but they would be in the minority now, slotted into the ancient warrior culture of the plains and moulded around it. That might bring problems of its own, of course, but it evaded the chief anxiety of the early days.

‘We would die out,’ the primarch murmured, remembering the time of transition. ‘That was the risk. That we’d be swallowed. All… this, gone. I’ll say this for

Him – He didn’t make us change.’

Hasik chuckled. ‘We’re still scared of that?’

The Khan looked at him sharply then, as if wondering just what that meant, before seeing it had been said in jest, a query fuelled by rosewine. Hasik was no longer supplying wholly dispassionate counsel, and his eyes glistened a little more strongly than usual.

‘Keep an eye on that one for me,’ the Khan said, reaching for more meat and watching the golden warrior melt back into the firelit crowds. ‘Find me more fighters like him, and we’ll never have to fear anything again.’

Over the next few days, the monastery-bastion bristled with activity. The presence of the Khan was a rare event and every official and master-at-arms was determined to make the most of it. It was forgotten by some that the primarchs were not only fighters – they were generals commanding immense forces, and their attention was as often consumed by the business of maintenance and diplomacy as it was in open warfare. The administration of Chogoris was something that the Khan reserved the last word on, and so regional governors were given audiences to update him on the ebb and flow of conflict between the tribes, the status of the growing orbital defence grid, the arrangements made to keep off-worlders away from the pristine hinterlands. Mechanicum adepts gave him lengthy discourses on the final phase of Quan Zhou’s armament, and Imperial Army representatives gingerly requested more data on expeditionary fleet forward planning, so that they could do better in their attempts to keep up with the White Scars’ dizzying rate of conquest.

Most of all, there was the development of the Legion’s fighting force to consider. More combat vessels for the Legion were being constructed across the Imperium’s forge worlds, and all would find their way to Chogoris sooner or later. They would need to be stocked with warriors at the peak of their training and overseen by veterans lifted from active-service brotherhoods. The movement of so many legionaries, together with their colossal amounts of equipment and supplies, was daunting, especially for a people who had never prided themselves on the careful keeping of records.

Two Metaphysical Blades

Two Metaphysical Blades Valdor: Birth of the Imperium

Valdor: Birth of the Imperium JAGHATAI KHAN WARHAWK OF CHOGORIS

JAGHATAI KHAN WARHAWK OF CHOGORIS Stormcaller

Stormcaller Child of Chaos

Child of Chaos The Lords of Silence

The Lords of Silence Daemonology

Daemonology Swords of the Emperor

Swords of the Emperor Wrath of Iron

Wrath of Iron Brothers of the Storm

Brothers of the Storm Horus Heresy: Scars

Horus Heresy: Scars The Sigillite

The Sigillite The End Times | The Fall of Altdorf

The End Times | The Fall of Altdorf The Path of Heaven

The Path of Heaven Master of Dragons

Master of Dragons WH-Warhammer Online-Age of Reckoning 02(R)-Dark Storm Gathering

WH-Warhammer Online-Age of Reckoning 02(R)-Dark Storm Gathering Wulfen

Wulfen Battle Of The Fang

Battle Of The Fang Onyx

Onyx Watchers of the Throne: The Emperor’s Legion

Watchers of the Throne: The Emperor’s Legion Leman Russ: The Great Wolf

Leman Russ: The Great Wolf Vaults of Terra: The Carrion Throne

Vaults of Terra: The Carrion Throne Siegemaster

Siegemaster STARGATE ATLANTIS: Dead End

STARGATE ATLANTIS: Dead End Scars

Scars The Empire Omnibus

The Empire Omnibus Blood of Asaheim

Blood of Asaheim