- Home

- Chris Wraight

Blood of Asaheim Page 26

Blood of Asaheim Read online

Page 26

He turned his gaze to Hafloí, who still wore an expression of shock. No doubt he was used to Blood Claws settling things in such a way, but Hunters were another matter.

‘Can you walk yet, whelp?’ demanded Gunnlaugur.

Hafloí seemed briefly uncertain, but nodded.

‘Good,’ said Gunnlaugur. His senses were returning. He felt clarified. ‘The canoness will be wondering where we are. We need to go.’ He shot a savage look at Ingvar. ‘We’ll settle this later. For now, survival.’

The pack looked back at him. They listened. In a strange, primitive kind of way he’d established his authority again.

Is that the best we can do? he thought to himself, not knowing how he would answer that, if pushed. Is that really – still – how these things are done?

‘Stay with Fjolnir,’ Gunnlaugur ordered Ingvar. ‘Let your blood cool while you’re in here. He needs guarding, and I’ll not have the Sisters discovering this.’

Ingvar nodded curtly, his expression torn between residual belligerence and the sullen acceptance of defeat.

Then Gunnlaugur swung round to the rest of the pack. The flow of blood raging around his system banished the weariness of the night’s work. There would be time to reflect on his choices later; for now, battle called again.

‘The rest of you, with me,’ he said, reaching for his helm. ‘We have a war to fight.’

With the departure of the pack, the apothecarion fell into near-silence. Baldr remained prone on the slab, his face grey and pallid. Unseeing eyes stared up at the ceiling, their pupils shrunk into mere specks of black. Even the golden irises, normally so vivid and reflective, looked washed out.

After a while Ingvar came over to stand beside him. His own face, a criss-crossed mass of bruises and lacerations, scarcely looked healthier than Baldr’s. He stooped, resting his hands on the edge of the table and bringing his head down closer to his brother’s.

Grief marked his severe features. He felt suddenly older, as if the cares of centuries had only then chosen to etch themselves on his genhanced flesh.

‘Brother,’ he whispered, as if speaking to him could bring Baldr out of the grip of his deep coma.

If he died there, it would be a terrible death, one every Son of Russ would shudder to hear of. No glorious last charge, no defiant stand, just slow capitulation to corrupting poisons within the walls of a mortal fortress.

Ingvar’s body ached. He could feel the blood on his skin thickening into scabs. Already the brawl seemed like a trivial, stupid thing; something born out of grief and guilt, something to be put aside and forgotten.

Some things, though, were more important.

‘Brother,’ said Ingvar again. He reached for the soul-ward at his breast. Despite Gunnlaugur’s furious assault it remained intact, as did the Onyx skull beside it. ‘You should not have given me this. It was yours, and I should not have taken it back.’ His eyes lowered. ‘But it was freely given. Is that not the way of our kind? To seal blood-debts with trinkets? I thought it was a way back for me. That was why I took it.’

Ingvar’s eyes flickered out of focus, their gaze uncertain.

‘I believed I could come back. I truly believed it. I wear them both now – my two lives, intertwined, interdependent. I thought I could keep them in balance.’

He looked around him then, as if suddenly nervous others might be listening. The apothecarion gazed back at him, deserted, echoing with antiseptic emptiness. Baldr’s blank expression registered no change.

Ingvar lowered his head further, keeping his voice to little more than a hiss.

‘I have to tell someone,’ he said. ‘If we are both to die here, far from the ice and unmourned, I have to tell someone. You will not remember. No vow is broken.’

Baldr’s face was unmoved, locked in the rigid grip of paralysis. His sickly features seemed carved from granite.

Ingvar paused, poised over what felt like a precipice. Heartbeats passed; his own strongly, Baldr’s almost undetectably.

‘I no longer believe, brother.’

Ingvar’s voice almost broke as he spoke those words. His hands gripped the side of the table. Horror filled his heart, horror that he had spoken such a thing out loud. Until then he had never done so, not even in the privacy of his cell’s solitude. The psycho-conditioning of the Adeptus Astartes was so ferociously strong.

But not unbreakable.

‘I no longer believe,’ he said again, more firmly.

It was less terrible the second time. Like unlocking a door into a hidden chamber of forbidden secrets, more thoughts spilled out, tumbling after the first one. He had broken the taboo; the totem had been cracked. After that, anything was possible.

‘We were seven,’ he said, no longer staring at Baldr’s static features but seeing things far away. ‘Just like Járnhamar, we were seven. Callimachus of the Ultramarines, Leonides of the Blood Angels, Jocelyn of the Dark Angels, Prion of the Angels Puissant, Xatasch of the Iron Shades, Vhorr of the Executioners, Ingvar of the Space Wolves. We were Onyx Squad.’

Ingvar smiled softly.

‘We did not call ourselves that. Halliafiore gave us the name. He gave us our missions. He gave us plenty.’

As he spoke he heard the faint noises of the apothecarion machinery working around them – the hum of rebreathers, the drip of saline valves, the slow click of medicae-cogitators. The chamber itself seemed to be listening to him.

‘For a while I held on to the past. I kept to the old ways, I walked the path of the ice. I learned to doubt slowly. Callimachus was patient. I think he liked me, for all the pain I gave him. He believed I would see the virtue of the Codex if I could be shown how it worked. He was right about that, at least at first. It was painful to see myths unravelled. Do you remember when we used to laugh at other Chapters? Of course, we were different. Nothing so hard, so cold, as the soul forged on Fenris.’

Ingvar bowed his head lower. He stared at his own clenched fists.

‘To do what we do, we have to believe. We have to believe there is no alternative, that our destiny is sacred, set apart from the start. That is what we are told in every saga and forced to learn by every Priest.’

Ingvar reached up for the soul-ward again, clutching it tight and straining the chain around his neck.

‘But what if the myths are broken?’

He remembered Bajola’s contempt.

Myths.

‘I have seen things, brother. I have seen star systems burning. I have heard the screaming of a billion souls. All of them, screaming. We couldn’t shut it out. I still hear them.’

Ingvar’s right hand started to shake. He let go of the soul-ward and clamped his gauntlet firmly against the steel.

‘There are weapons, Fjolnir, things you would not believe. There are devices so powerful that even to speak of them outside the Deathwatch is to earn execution. Only Callimachus could have been trusted to give the order to use them. He would have done his duty even if it meant tearing out the heart of his own primarch. Could I have done it? I do not know. But he did. He gave the order, and we used those things on our own kind, burning them into atoms so that the Great Devourer would not be able to feed on their corpses.’

The cogitators ticked gently. Baldr’s chest rose and fell. The rebreathers hummed.

‘Then we had to watch it come. The Shadow, so vast it might have been another star system in motion. We had to watch it move over us, blind to our presence, day after day, huddled away from its wrath, watching its living ships ply across the void, watching them crawl into the warm heart at the centre of the galaxy.’

Ingvar shuddered at the memory.

‘Endless,’ he whispered in horror. ‘Endless.’

Baldr’s ashen face showed no tremor of recognition. He lay limply, locked in a sealed world of pain.

‘After that, after seeing that, I no

longer believe,’ Ingvar said again. The third time, it was almost easy.

He straightened slowly, pushing himself away from the slab.

‘If there is to be victory, brother, I cannot see it. I cannot remember how it feels to keep my blade in hand, glorying in my service to the Allfather. All I see is the living ships. All I see is what they made us do.’

His voice cracked again.

‘I thought I could come back. I thought I would remember again once I was among you. I do not blame Gunnlaugur for pushing back, he is as lost as the rest of us. I blame myself for hoping.’

He smiled again, a pinched, wistful narrowing of the lips.

‘And I blame you, Baldr. You fed my hope. As long as you remained as you were in my mind’s eye – so calm, clear, so noble – coming back did not seem impossible. But it is. I understand that now.’

He wiped a thickening trail of blood from his upper lip. He could feel his broken skin beginning to swell.

‘You must fight this. You still have a place here. If I fight for anything now, it is for that. I would see you restored before the end.’

Ingvar leaned down again for a final time, bringing his lips close to Baldr’s ear, ignoring the stink of putrescence.

‘Remember how you were. Remember the way you smoothed the way between quarrelling brothers. You always commanded your animal spirits so much better than we did. Remember that strength. Do not die here, brother. Remember yourself.’

Baldr made no response. His open eyes stared sightlessly at the ceiling, their lustre gone.

‘Remember yourself,’ he said again, his voice a quiet urging. ‘I no longer believe, but you must do. For the sake of what is left of this pack, you must believe.’

As Ingvar spoke, he felt the first spike of tears at the corner of his eyes.

It might have been fatigue. It might have been shame, or frustration. It was weak, out of character; but then so much of what he had done had been out of character, and for as long as he could remember.

Ingvar bowed his head.

‘For the sake of us all,’ he said, his voice soft and pressing. ‘Come back.’

Chapter Eighteen

They came with the sun. As the sky turned rust-red, then flesh-grey, then a clear, deep, cloudless blue, the plains began to fill with the armies of ruin. Slowly at first, as the advance units crawled across the dust, then with growing frequency as the main detachments caught up and the day waxed towards noon. They went warily, watchfully, before finally digging in several kilometres clear of the walls.

Canoness de Chatelaine watched them from atop the fortifications of the Ighala Gate. As the hours passed, she watched the air turned brown from the clouds of dust they threw up, and smelled the hot, putrid stench of their bodily corruption. The sun beat down, making her sweat even within her armour.

Callia stood beside her, as well as six of her Celestians in their dark battle-plate. All along the walls, running away from the gate-bastion in either direction, Guardsmen and Battle Sisters had taken up positions behind the battlements. The Guardsmen wore full-face gas masks and sealed carapace armour. Few of them spoke. Few of them moved. They stood quietly, expectantly, nervously, watching.

‘Word from the Wolves?’ asked de Chatelaine, her eyes fixed on the gathering army out on the plain.

‘On their way, canoness,’ said Callia. Her voice was more nervy than usual.

‘Their wounded?’

‘One warrior. He remains in the citadel. The others will fight.’

De Chatelaine nodded. ‘Good. For what it is worth, good.’

She couldn’t summon up much more than a token enthusiasm. This day had been coming for months. It had filled her dreams every night since the plague-ships had first appeared above her world. In her heart she had never believed victory to be possible. Now, seeing what the enemy had created and was capable of deploying, that belief became a certainty.

Privately she had always doubted that Gunnlaugur and his savages really understood just what volume of horror had been unleashed on Ras Shakeh. Perhaps their raw confidence was just an act, a show of defiance in the face of inevitable defeat. Perhaps they truly believed they could turn the horde back. In either case, their arrogance had only a superficial charm.

‘Nothing remains to be done,’ she said coldly.

It was true. The outer walls were fully manned and the defence towers stocked with huge quantities of ammunition. The engineering works in the lower city had been completed. Fire lanes had been gouged through the interlocking network of shadowy streets; pits had been dug in concentric lines ready for the promethium that would be pumped into them at a moment’s notice. Explosive lines snaked their way through the hab-units and gun-clusters, ready to be ignited as the enemy reached them.

De Chatelaine felt a soft swell of pride as she cast her eyes over what had been achieved. Her Sisters had laboured well, keeping the spread of contagion down and mobilising the workforce. The Wolves, particularly the big one with the scars, had accelerated the work enormously, but the bulk of the lifting had still been done by mortal soldiers under her command. Given the time they had had to work in, and the conditions, it was an achievement worth taking pride in.

She ran the numbers through her mind one last time. Twenty thousand Guardsmen were on the outer perimeter, almost all stationed along the walls or in the defence towers. Sixty Battle Sisters stood with them in ten-strong squads to stiffen their resistance. A reserve line of ten thousand Guard and militia, plus the few mechanised units they possessed, were posted within the terraces of the lower city in staggered detachments. Six Sisters were billeted in the cathedral with Palatine Bajola, with the remainder of the Sororitas contingent up in the Halicon, together with the final five thousand Guard troops, ready to oversee the withdrawal to the citadel should they be forced into a last stand at the summit.

De Chatelaine lifted her helm and looked out again at what faced them. The enemy had dug in several kilometres out, far beyond the range of the guns on the perimeter wall. Her helm-lenses zoomed in as she squinted into the hot light.

Their formations were huge. Battalions of infantry, each one many hundreds strong, marched up out of the dust. They arranged themselves in ragged squares, each one headed by contagion-mutated command squads bearing rough-hewn standards and skeletal trophies. The air around them was thick with a screen of dust and spore-clouds. The troops wore a motley collection of armour – rusting iron plates, looted Guard uniforms, strangely warped and merged creations of bolted metal and stretched sinew.

De Chatelaine couldn’t zoom in close enough to see their faces, though she knew well enough what they would be like: listless, bloated with tumours, the flesh pressing out from the stitched joints in their leather hoods and gas mask-helms, stained green from the clouds of filmy murk that swam behind their eyepieces. Some of those troops would have been landed from the plague-ships; others were new recruits, infected and enslaved during earlier fighting. They were all equally lost now; only death, in some cases for the second time, would release them.

Already the host of plague-bearers comfortably outnumbered the defenders on the walls and more regiments were arriving all the time. She saw huge, slab-sided troop carriers smoking and rolling into position, vomiting more diseased soldiers from their flanks before shuddering back away from the front line to ferry more in. Plumes of noxious smog rolled and boiled amid the drifting dust, staining the clear blue of the sky with a wash of swimming filth.

De Chatelaine swept her gaze back and forth, scouring the front line for signs of more formidable fighters. She knew they would be there, somewhere, stalking amid the endless ranks of mortal fodder. She’d seen footage of great striding horrors, each three times the height of a man and almost impervious to pain or damage. She’d heard stories of hovering drones that buzzed across the battlefield spreading gouts of flesh-melting blooms, and swarms of fist-s

ized insects that latched on to faces and bit through flak-jackets.

She saw none of those things. They were being held back at the rear of the gathering host, ready to be unleashed when the defences were reeling under the weight of attacking numbers.

De Chatelaine smiled thinly. It was what she would have done, given the luxury of such overwhelming force.

And of course there was the matter of the Plague Marines. She knew that one had been destroyed by the Wolves; she doubted it was the only one. Perhaps only a handful had been landed, or perhaps dozens had.

No way of knowing until the fighting started.

‘We’ve been waiting too long,’ said Callia grimly. ‘I find myself wishing for it to begin.’

De Chatelaine nodded. ‘Which is why they will linger.’

‘Maybe this time will be different.’

‘No. They wish for our fear to grow.’

Even as she spoke, a strange, half-audible noise drifted across the plains towards them. At first it sounded like the eddying drift of the desert wind. Then it clarified – a whispering chant, hissed through broken lips and filtered by spore-thick rebreathers. Thousands of voices were murmuring in unison, mournfully repeating the same words over and over again.

Terminus Est. Terminus Est. Terminus Est.

‘The end,’ said Callia. ‘They are telling us that this is the end.’

De Chatelaine listened. ‘Maybe,’ she said. ‘Or perhaps it has some other meaning. Who knows?’

She spoke deliberately lightly, as if it mattered not what jabbering nonsense those pustulent mouths spat out. For all that, the mournful repetition quickly became grating. It preyed on the nerves, irritating like the sting of a gadfly. The army kept up the chant, whispering and chattering like ghouls.

She straightened, pushing her shoulders back and keeping her spine straight. That was how she intended to stay until the fighting began – standing tall, looking the enemy in the eye.

Two Metaphysical Blades

Two Metaphysical Blades Valdor: Birth of the Imperium

Valdor: Birth of the Imperium JAGHATAI KHAN WARHAWK OF CHOGORIS

JAGHATAI KHAN WARHAWK OF CHOGORIS Stormcaller

Stormcaller Child of Chaos

Child of Chaos The Lords of Silence

The Lords of Silence Daemonology

Daemonology Swords of the Emperor

Swords of the Emperor Wrath of Iron

Wrath of Iron Brothers of the Storm

Brothers of the Storm Horus Heresy: Scars

Horus Heresy: Scars The Sigillite

The Sigillite The End Times | The Fall of Altdorf

The End Times | The Fall of Altdorf The Path of Heaven

The Path of Heaven Master of Dragons

Master of Dragons WH-Warhammer Online-Age of Reckoning 02(R)-Dark Storm Gathering

WH-Warhammer Online-Age of Reckoning 02(R)-Dark Storm Gathering Wulfen

Wulfen Battle Of The Fang

Battle Of The Fang Onyx

Onyx Watchers of the Throne: The Emperor’s Legion

Watchers of the Throne: The Emperor’s Legion Leman Russ: The Great Wolf

Leman Russ: The Great Wolf Vaults of Terra: The Carrion Throne

Vaults of Terra: The Carrion Throne Siegemaster

Siegemaster STARGATE ATLANTIS: Dead End

STARGATE ATLANTIS: Dead End Scars

Scars The Empire Omnibus

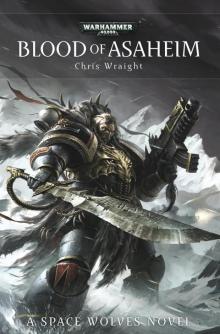

The Empire Omnibus Blood of Asaheim

Blood of Asaheim